Home | Slovakia | Slovakia | A Brief History of Slovakia

When we look at the map of Europe, we can see that Slovakia is in the very centre of it. As a matter of fact, the geographical centre of Europe can be found in Slovakia, nearby the old mining town of Kremnica.

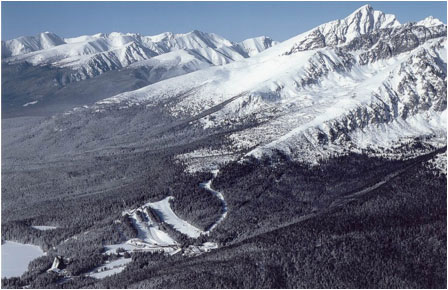

The High Tatra Mts.

The country’s inherited character has shaped its rich history. A number of civilisation layers have been laid down in the territory of the present-day Slovak Republic. Especially fascinating is the touch of the old Celts – in the 1st century BC, there was a Celtic Oppidum in the area of the capital city Bratislava, a settlement where the coins of Celtic Princes Biatec and Nonnos were minted. (You can find the original shape of the coins on the current Slovak five-crown coin!). The Celts were replaced by the old Romans, when they built the fortified system of the Roman Empire called Limes Romanum in the middle Danube region. They left the Roman military station of Gerulata nearby Bratislava and an original Roman inscription on the Trenčín Castle rock made by the 2nd auxiliary legion, which had a winter camp here at the turn of 179 –180 AD. Slovakia’s territory was undoubtedly made most famous by Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, who wrote his Writings to Himself (also called Meditations) at the Hron (Granus) River in the area of Levice. The German tribes of Markomans and Quads, as well as Huns and Avars, passed through our territory and since the 5th century Slovakia has been consistently inhabited by Slavic population. In the 6th century, the Slavs created their first state formation – the Samo Empire – the capital of which was Wogastisburg located in the area of the present-day Bratislava. The first separate state – the Great Moravian Empire, was established by old Slovaks in the 8th and 9th century, when Princes Pribina, Rastislav and Mojmír, and above all King Svätopluk consolidated an influential state formation. Written reference Rastislav, the ruler of Great Moravia at the Devín (Dowina) Castle (10 km from Bratislava at the confluence of the Danube and Morava rivers) can be found in the Fuldish Annals. Archaeological excavations at the Bratislava Castle, where the talks of the two great statesmen will be held, prove the presence of a Great Moravian fortification here from the times when King Svätopluk had his seat here, known from an entry in the Italian Cividale Evangelistary. A statesmanlike act of Prince Rastislav was the invitation of two scholars – Constantine (Cyril) and Methodius – from Constantinople in 863, who created the old Slavonic writing and translated the Bible from Greek. The philosopher Constantine wrote his most beautiful work – a poem in Old Slavonic entitled Proglas, as a foreword to the translation of the Bible. Since this was the most inspiring period for Slovaks, the Constitution of the Slovak Republic of 1 September 1992 refers to the Cyrillo-Methodian traditions in its Preamble.

After the decline of the Great Moravian Empire, the territory of Slovakia became part of the Hungarian state. Since then the Hungarian history became part of the Slovak history, because both higher and lower Slovak nobility and Slovak noble families helped fortify and defend the border of the Kingdom of Hungary from invasions of Tatars and later Turks. As a matter of fact, two Slovak noblemen Hunt and Poznan belted the sword to the waist of Hungarian King Stephen I to mark that he was chosen the king. Already back then the Danube River and the Tatra mountains, between which the old Slovaks lived, became symbols of the Slovak country. A set of guard castles and fortifications was built in the Middle Ages, in particular in the Váh River basin, to protect the Hungarian land. The noble families, who maintained their Slovak identity and went down in history of Hungary, include the Turzo and Ileshazi families. Juraj Turzo received diplomats from Venice at his castle in Bytča and not only maintained frequent correspondence, but, being the Hungarian palatine, also held talks with world rulers.

Bratislava enjoyed particular prosperity under the rule of King Sigmund (1387-1437), who preferred it over Vienna and Budapest. When the Turks had forced Hungarian state power out of Budapest, after the defeat in the battle at Mohacs (1526) Bratislava became the Hungarian capital for two and a half centuries and a number of Habsburgs were crowned in St. Martin’s Cathedral, including Maximilian I, Rudolf II, Maria Theresa and Joseph II. That’s why there is still a golden crown atop the tower of St. Martin’s Cathedral. The Hungarian parliament held regular sessions in Bratislava and therefore servitude was abolished in our capital city in 1847-1848. Political leader of Slovaks Ľudovít Štúr, who endeavoured to achieve a confirmation of Slovak national identity, was a member of the Hungarian parliament as a deputy of the royal town of Zvolen. He worked as a professor at an Evangelical lyceum and published the first political newspaper – Slovak National Newspaper (1845-1848). After the first attempt to codify Slovak by Catholic priest Anton Bernolák, Ľudovít Štúr created modern Slovak grammar and literary language used by Slovaks today.

A little wooden church in Ladomír

Štúr, together with Jozef Hurban and Michal Hodža, stood up during the 1848-1849 revolution in an armed uprising against Hungarian oppression of the Slovak nation, when the Hungarian government ignored the cultural and political demands of Slovaks as a modern European nation. On 19 September 1848, they established the first Slovak National Council in Myjava, a legislative and executive body of Slovaks in the uprising. Jozef Hurban became the first Speaker of the Council. The Museum of Slovak National Councils is located in Myjava. In 1863, after establishing the Tatrín association, Slovaks founded an influential national cultural and educational institution in Martin called Matica slovenská, which was banned by the Hungarian Government in 1875.

Better times for the development of the Slovak national identity and cultural heritage came after 30 October 1918, when Slovakia deliberately joined the Czech Republic and created the Czecho-Slovak Republic through the Martin Declaration of Slovak political representatives. This was preceded by consistent political activity of Slovaks and Czechs abroad. Along with Professor Tomáš Masaryk, Slovak General Milan Rastislav Štefánik played a decisive role in the establishment of the free Czecho-Slovakia. The separation from the Kingdom of Hungary and the period of the first Czecho-Slovak Republic brought advancement to Slovaks in all spheres of life – economy, education, culture, as well as presentation of Slovakia abroad. Despite the benefits of the co-existence with Czechs, Slovakia remained an economic appendage to Bohemia. The Movement for Autonomy of 1938 was the first step towards sovereignty of Slovakia. Unfortunately, it emerged in the worst possible time, during the war. The Slovak Republic established on 14 March 1939 was under Hitler’s dictatorship and its leading representatives agreed to the deportation of 70 thousand Jews to concentration camps during its existence until 1945. For the sake of historic truth, it should be emphasised that the democratic forces in Slovakia prepared and declared the armed Slovak National Uprising against German fascists in Banská Bystrica on 29 August 1944. The Slovak war against the Nazi Germany lasted until the end of October 1944, when the partisans and Slovak soldiers had to surrender to the mountains. Being the second biggest European anti-fascist uprising, it laid foundations for the new democratic traditions of the Slovak nation. This is where the first thoughts of a fair arrangement of the Slovak-Czech relations after 1945 were born. Unfortunately, nothing changed after 1948, when the Communist dictatorship took over. The revival process initiated by the most famous Slovak in the world Alexander Dubček, which gave great hopes to Europe and the free world, was left uncompleted after the Soviet occupation. Despite this, Slovaks finally achieved the establishment of a federation and two republics. The documents creating the federation were signed at the Bratislava Castle on 30 October 1968. This created good conditions for the massive emancipation movement for the establishment of an independent Slovak Republic that emerged after the Velvet Revolution of 1989, which eventually led to the declaration of sovereignty on 1 January 1993.

Since then, the free parliament of an independent state – the National Council of the Slovak Republic – has its seat at Alexander Dubček Square in the neighbourhood of the Bratislava Castle and President of the Slovak Republic Ivan Gašparovič has his seat at Hodža Square in the historical building of Grassalkovich Palace, where Joseph Haydn once performed. A historic breakthrough for the Slovak Republic was 1 May 2004 – the date of accession to the European Union, as well as the fact that it became a member state of NATO. The summit of the two highest representatives of the USA and the Russian Federation in 2005 gives a new dignity to the capital city of the independent Slovak Republic and a hallmark of paramount importance to the Bratislava Castle. Slovaks are accordingly proud of the trust that has been placed in them. |